Welcome to the fourth and final installment of this year’s MA Quarterly Essay series, and Part 5 of an investigation into the symbolism of neck rings in African ornamental culture.

In Part 1, we examined the occurrence of neck rings in different African cultures.

In Part 2, we used proverbs and poetry to explore African beliefs about the symbolism and aesthetic appeal of the neck with the attendant connotations of power, vulnerability and beauty.

In Part 3, we focused on the the Zulu of South Africa to examine the cultural significance of neck rings their traditional culture.

In Part 4, we discovered the intriguing folklore and impressive social organization around the odigba, the royal neck rings of Nigeria’s Edo people.

In this essay, we turn our attention to the AmaNdebele of South Africa to examine how neck rings act as an indicator of health and wealth.

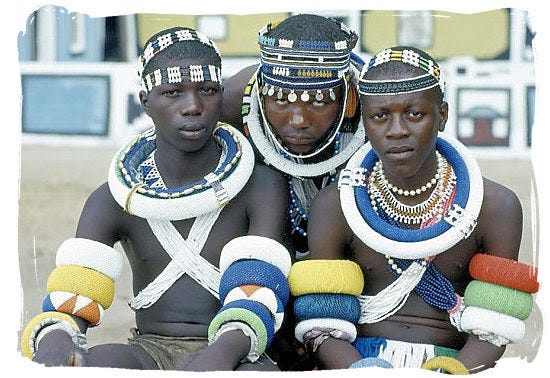

If you search Google Images for the word “Ndebele”, the results will feature strikingly beautiful women with cheekbones to kill for, dressed in vividly colored, geometric-patterned clothing, and wrapped in similarly designed blankets. You will also notice the gleaming copper and brass rings, or large beaded hoops around some of their necks, arms and legs. One of these women will most likely be Dr. Esther Mahlangu, an artist from Mpumalanga village, South Africa. She is known for her intricate murals derived from her people’s tradition of painting the exteriors of their homes. She is also the subject of one of the most iconic images to emerge from the African continent: that of a Ndebele woman, neck elegantly poised to display her brass neck rings.

The Ndebele Tripartite

The Ndebele of southern Africa are divided into three groups: The Southern and Northern Transvaal Ndebele who are South African (also known as the AmaNdebele), and the Ndebele of Zimbabwe. The Ndebele trace their origins to Mnguni, the forefather of the Nguni people. Mnguni’s four sons: Xhosa, Luzumane (Zulu), Swazi and Ndebele founded the main Nguni groups. Ndebele and his followers migrated north from Kwazulu-Natal where his father and brothers historically settled. They eventually reached Emhlangeni (present day Randfontein) and then subsequently, spread to Wonderboom (KwaMnyamana) and various areas of the then Transvaal province of South Africa (present-day Gauteng, North-West, Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces). Generations later, at the end of the reign of Chief Musi, one of Ndebele’s descendants, a succession fight between Manala (son of Musi’s first wife) and Ndzundza (son of his second wife) split the Ndebele. Contested oral traditions hold that the fight arose when Musi, too old to tell his sons apart, was tricked into giving the royal namrali oracle - an incontestable symbol of kingship - to Ndzundza instead of Manala as tradition required. In other accounts, Musi deliberately made Ndzundza his heir instead of Manala. Either way, chaos ensued. The brother’s fought, polarizing the AmaNdebele people into two main factions: the Manala and the Ndzundza. The hostilities persisted to as recently as 2014 when the South African High Court ruled that, based on what is known about the history of the people, AmaNdebele kingship exists and resorts under the lineage of Manala, not the Ndzundza-Mabhoko paramountcy.

The Mfecane, southern Africa’s most notable period of political and social upheaval which ravaged the region from the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century also affected the Ndebele people. After defeat by the Ndwandwe, Mzilikazi, a powerful Khumalo1 chief first formed an alliance with, but eventually defected from Shaka of the Zulu2. To escape retribution, Mzilikazi migrated north with his people. As they travelled, they systematically incorporated smaller communities into their fold either by raiding them or offering weaker groups their protection. When they eventually encountered the divided AmaNdebele, Mzilikazi overpowered them, further splitting the Manala faction into three subgroups. Mzilikazi’s group spent enough time with the Ndebele to absorb their culture and customs. However, persistent attacks from the Zulu kingdom and general instability in the area forced him to migrate even further north. His followers, who now included significant numbers of Ndebele people, settled in the Matopos region of present-day Zimbabwe.

While they share the same name, and common or proximate origins, there are enough differences in language and material culture between the three Ndebele peoples to distinguish them from each other. The brightly patterned clothing, murals and distinctive accessories commonly associated with the Ndebele, come from the AmaNdebele.

Flourishing Trade, Emerging Fashion

Like other southern African peoples, the AmaNdebele were part of the trade networks along the East and Southern African coast, and so, glass beads from India, as well as copper and its alloys were highly valued items for which ivory and other indigenous materials were traded. These highly prized materials were then used by the people for transactions or worked into adornments which indicated the status and relative wealth or prosperity of their wearers.

Good Health, Great Wealth

AmaNdebele people wear rings around their necks, arms, legs and waists as part of everyday or ceremonial garb. There are three kinds of AmaNdebele neck rings: the ijogi (which means “yoke”), the isigolwane (also isirholwani or iirholwane) and the idzilla. Ijogi and isigolwane are hoops traditionally made by weaving grass into a circle and covering it with colorful glass beads. Idzilla are copper or brass neck rings. Traditionally, ijogi were worn on special occasions while isigolwane were worn by young married women until the birth of their first child. This distinguishes them from the idzilla which are worn around the neck, arms and legs by older married women. In the past, an AmaNdebele man gave his wife idzilla after he built her a home and the number of idzilla indicated how wealthy the man was. AmaNdebele women wear their idzilla permanently as a sign of faithfulness to their husbands and can only remove them after his death. The AmaNdebele idzilla is similar to the paduang worn by Myanmar’s Kayan women. Unlike the AmaNdebele, however, Kayan girls start wearing brass neck rings as children.

By some accounts, neck, arm, and leg rings are also believed to be symbolic of rolls of body fat, a desirable trait to the AmaNdebele and many other African peoples. This association presumably comes from the idea that corpulence is indicative of good health and wealth in an environment of drought or war-related famines. Neck rings among the AmaNdebele are, therefore, a means through which people displayed their good health, and women their status and their husbands’ wealth. Isigolwane, for example, are worn by married women yet to bear children. This distinguishes them from older married women who wear idzilla, with the number of idzilla worn indicating how wealthy their husbands are.

In the past, idzilla were custom made by male craftsmen. The artform has died out over time, with the copper or brass rings replaced by more flexible rings made from plastic and other materials. Ijogi and isigolwane are also now made with plastic hoops covered with beads.

Nonetheless, the ijogi, isigolwane, and the idzilla remain beloved accessories to the AmaNdebele. They are still widely used in the ceremonial context and have also established themselves as a must-have modern African fashion accessory across the continent and the world.

References

Afọlayan, Funso S., and Funso S. Afolayan. Culture and customs of South Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. Page 13-15

Bhebe, Ngwabi MB. Ndebele trade in the nineteenth century. Journal of African Studies 1.1 (1974): 87.

Boyd, Craniv Ambolia. Ndebele Mural Art And The Commodification Of Ethnic Style During The Age Of Apartheid And Beyond. Freie Universitaet Berlin, 2017. Page 32

Determination on Manala-Mbongo and NdzundzaMabhoko Paramountcies: Report from the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims in the High Court of South Africa, Gauteng Division, Pretoria.

Lye, William F. The Ndebele Kingdom South of the Limpopo River. The Journal of African History 10.1 (1969): 87-104.

Mashiyane, Zwelabo Jacob. Beadwork: Its cultural and linguistic significance among the South African Ndebele people. Diss. 2006.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo Jeremiah. Dynamics of Democracy and Human Rights Among the Ndebele of Zimbabwe, 1818-1934. Diss. 2012.

Smith, Andrew Cyrus, and Nomusa Dlodlo. Preserving the Ndebele dress code through the Internet of Things technologies. Proceedings of the Second African Conference for Human Computer Interaction: Thriving Communities. 2018.

Van Vuuren, Chris J. Iconic bodies: Ndebele women in ritual context. South African Journal of Art History 27.2 (2012): 325-347.

The Khumalo are a collective of autonomous clans of Nguni people who settled in the northern part of KwaZulu Natal province in present-day South Africa.

Chaka also used neck rings extensively.